Apathy and pessimism won't save us

by Rob ParsonsApril 9, 2009

"I always wake up at the crack of ice." - Joe E. Lewis |

|

|

“In your life expect some trouble/ But when you worry you make it double/ Don’t worry, be happy....”

–Bobby McFerrin

I’ve

been worrying lately. I know it doesn’t serve my best interests, or

anyone else’s, to give in to the swirling, sucking eddy of gloom about

the economic downturn, the trashing of the environment and the plunder

of the planet’s natural resources.

Yet

it’s as though I’m hearing a Doomsday clock ticking in my ear that I

cannot ignore. I’m reminded of Tock, the watchdog in Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth, who helps get Milo back on course after he found himself waylaid in the Doldrums by not thinking.

I

can understand the part about not thinking, that ignorance is bliss.

Thoughts, after all, are a force to be reckoned with.

I’ve

learned that time spent in the self-indulgence of fear, worry or

cynicism is time wasted—unless it serves to impel me to get out of my

own rut, to change my behaviors and state of mind.

I’ve learned

that my voice matters, that my efforts matter. I believe in the ripple

effect. When others join in and toss a pebble in the same pond, mere

ripples may become waves of change.

I’ve witnessed the absolute

thrill of individuals and grassroots organizations joining hands to

bring about positive change, as explicated in Paul Hawken’s uplifting

book Blessed Unrest. I understand the divine timing of the universe, wherein everything is unfolding and evolving exactly as it should.

But

something deep within me wants to cry out to alert those who are

sleepwalking through the 21st century, oblivious to the precipice upon

which we stand.

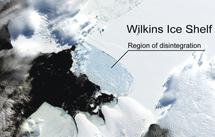

Sumatran orangutan and coral polyps,

spotted owl and Chinese panda, giant Bluefin tuna and the Hawaiian monk

seal—all are in danger of extinction. Meanwhile, the rise of carbon

dioxide levels and those of other greenhouse gases has led to ocean

acidification, violently unpredictable planetary weather and, recently,

the collapse of the Wilkins Ice Shelf in Antarctica. That occurrence

will allow newly formed icebergs to move freely into the open ocean,

and is the seventh Antarctic ice shelf in that area to retreat or

collapse in recent years.

We have fouled our nest to the extent

that it has become unhealthy not only for us, but for millions of other

species. And yet we don’t seem motivated enough to radically change our

arrogant consumptive and procreative ways. Like Spike Lee’s character

at the end of his 1988 film School Daze, I want to shout, “Wake up, everybody!”

I

attended two events last weekend that gave me cause for reflection. The

More Fish in the Sea gathering at Maui Community College was an epic

eco-fair, with 30 informational booths plus hula, music, speakers

sharing traditional cultural and environmental values and ocean-themed

movies after dark. The overriding theme was that we all must work

together to protect and restore the vitality of our ocean eco-system

and the many creatures it sustains.

I learned that proposed

legislation for banning the unlimited collection of aquarium fish

failed for the second straight year, when Rep. Ken Ito refused to hear

the bill in his Water, Land & Ocean Resources Committee. I was

reminded of how many years it took to pass even a partial gill net ban,

and wondered how many turtles, monk seals and non-target species were

killed as by-catch in the interim. I winced when I heard that funding

for the Natural Area Reserve System has gotten the axe, in another

shortsighted budget-balancing effort, which could also cost neighbor

islands their fair share of transient accommodations tax revenue.

While

many families showed up, on a last outing or fling before the end of

spring break, there was a notable absence of decision-makers—not the

mayor or a single county councilmember or state legislator was to be

found. In large part, this was an expanded example of the island’s

eco-heroes preaching to the choir. Nevertheless, it was a significant

and impressive first step in addressing these vital concerns.

On

Sunday, I flew to Kona then traveled the coral-and-lava grafittied

highway up to Kawaihae to present information on open ocean aquaculture

at a meeting with at least 50 community members in attendance. The

audience listened to pro and con sides of raising huge amounts of ahi

in deepwater fish cages, and heard from an existing fish farm, Kona

Blue.

Something must be done, they said, to compensate for how

we have over-fished the majority of the fish species in the ocean.

While this may be true, I replied, that shouldn’t give carte blanche

for launching immense operations with untested technology in an industry that has

been rife with environmental impacts..

The

question-and-answer period was illuminating, and a bit edgy. A member

of the Kanaka Council asked why Hawaiian cultural concerns weren’t

discussed, what benefit, if any, there was to island residents, what

part of lease payment goes to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and why we

should be asked to feed the rest of the world and not ourselves. His

questions went unanswered when the facilitator simply moved on to the

next questioner.

Another citizen said it’s necessary to examine

the whole system, including the increasing human population (as the

main component in declining fish populations). A former UH-Sea Grant

aquaculture advocate had stated that China is by far the largest

aquaculture producer in the world. Make no mistake, he said, about who

will be controlling the world’s economy and resources in the coming

years.

Finally, a questioner asked, “What is the impact of doing

nothing?” Implicit in his query was that trying to stop the project on

environmental or cultural grounds wouldn’t put sashimi on anybody’s

plate.

But to what degree can we continue to expect man-made

contraptions to offset the damage our species has wrought? Yes,

something must be done—and soon. But continual dependence on scientific

advances and venture capital gambles won’t save us from ourselves if we

don’t abide by the laws of the natural world.

I was encouraged

to see that world leaders, assembled in London for the G20

Climate Change Summit, met with Prince Charles to hear his call for

emergency action to halt the rampant destruction of the world’s

rainforests and the resultant release of carbon dioxide. Prince Charles

founded the Prince’s Rainforest Project a few years ago, strategizing

along with dozens of eco-organizations who have fought an uphill battle

against widespread deforestation in the Amazon, Africa, Malaysia and

Indonesia.

But are world leaders listening? Certainly the media

gave more coverage to Michelle Obama’s latest outfit than the

Prince’s proclamation. Corporate greed, fueled by World Trade

Organization policies, have steamrolled local cultures and natural

resources under the guise of offering economic opportunities.

On the home front, letters to The Maui News regarding a proposed ban on big-box stores are revealing more

shortsighted thinking. One writer calls it un-American to limit

competition, and says consumers should be allowed to decide where they want to shop.

Never mind that the corporatization of Maui means a

continuing loss of our identity and sense of place, so Dairy Road-type

urbanscapes look like Anywhere, U.S.A. with a few palm trees added.

Ignore that dollars spent on items at these hulking chain stores leave

the island to fatten the coffers of the wealthiest companies and their

CEOs. Forget that small stores that have survived on Maui for

generations have fallen victims to cheap prices.

If inexpensive

consumption of consumer goods is our bottom line, the outlook for our

island paradise isn’t very sunny. It’s time to treat the “affluenza”

epidemic with some healthy doses of local, sustainability tonic.

Though

bitter to swallow, it will require meaningful shifts in our values and

behavior. Now is the time for citizens to be fully awake and engaged to

ensure that all the emphasis on economic stimulus doesn’t lead to

starvation of social and environmental justice efforts. This is the kuleana that we all share—to malama the land, the sea and one another.