As the massive Wailea 670 project moves through the County Land UseCommittee, we talk with three local activists about how they've awakened to the danger sposed by over-development

August 23, 2007

The sun-baked slopes and shoreline of what is now known as the Wailea and Makena areas was once home to a series of fishing villages. The old Makena Road was part of the Pi’ilani trail built in the 1500’s, linking coastal villages all the way from Kaupo to Keawakapu. Archeological studies indicate that many of these sites had continuous habitation from the 15th to the 20th century.

Charles Pili Keau, born in Wailuku in 1927, had a keen interest in these ancient sites. He accompanied the Bishop Museum’s Dr. Kenneth Emory during Emory’s review of Maui Island cultural sites in the 1970’s.

Activists, left to right: Kenneth "Braddah" Ho`opai, Walter Tau`a, Chisa-Lee Dizon, Carlo Elaban, David K. Ho`opai, Samson Harp, Koko, and Ilona Rahn. In Front: Kamanalani Geddes and Jonah K. Ho`opai PHOTO: Pietro Ortiz |

|

|

Keau spoke about the findings of their studies at a 1985 Planning Commission hearing about the abandonment and closing of a section of the old Makena Road.

“Many fishing villages are connected by the ancient road,” Keau said. “Starting from Keoneoio, the road runs along Kalihi, Paalua, Maonakala and Kanahena villages. Each village has a heiau located near the road. From Kanahena, the road goes to Pa‘ako, then past another village near Pu‘u Olai—I don’t know the name of that village, but it’s at village with a three-sided heiau, one side open to the sea—and on to a large village complex which is on the site of Seibu’s golf course. I think it was a large village because there are three heiau and numerous terraces.”

Other than historical records, very little evidence remains of these cultural sites. A few structures have been preserved, but are grossly out of context. Some even sit as landscape features in the yards of multi-million dollar condominiums or homes. The relevance of these sites to the Hawaiian history of the region has largely been cut off.

Recent development proposals of large tracts of land in South Maui have created another sort of rift in the community. Those supporting construction jobs, real estate inventory and affordable housing possibilities have heard strong opposition from others favoring conservation of dwindling water resources, improvements to infrastructure, protection of reefs and preservation of cultural and botanical sites.

Cultural sites preserved as landscape features in the yards of multi-million dollar condominiums and homes. Photo: SaveMakena.org |

|

|

At recent Council Land Use Committee hearings for rezoning of the Wailea 670/Honua‘ula project, which calls for 1,400 homes and a private golf course, the standing-room-only audience included dozens of young Hawaiians. While some merely listened, others spoke up, lending their passionate voices to the debate. Outside in the hallway, some talked story with friends or relatives who were told to be there and support the project by their construction bosses.

Inspired by what they’d heard about archeological sites and a vital remnant dryland forest habitat on the Honu‘ula property, some of the Hawaiians chose to exercise their native rights to access the property.

In 1995, a landmark Hawai‘i Supreme Court ruling affirmed that Hawaiians retain cultural rights on private land that is undeveloped. Kona activist Jerry Rothstein founded PASH—Public Access Shoreline Hawai‘i—which challenged the Kohanaiki project, originally proposed in the early 1990’s to develop a hotel and golf course. The court’s decision over “PASH rights” ensured that Native Hawaiians have a say in what happens to land they need for religious uses and for “gathering rights” such as the traditional collection of plants, wood and natural resources that supported their ancestors.

On a recent Sunday morning, Samson Harp, Ilona Rahn and Chisa Dizon stood at a gate marked “No Trespassing—Wailea Resort,” part of a group that came to hike upon the lands once accessed by Hawaiian ancestors. They proceeded to explore lands proposed for development by Honua‘ula and Makena Resort investors.

Just returned to Maui after two years in Alaska, Samson Harp is an artist and owner of the Island Rootz tattoo shop in Kihei. He wears the image of the Hawaiian Islands, stretching from his left temple over his eyebrow. Harp says he got involved, “Because it’s the right thing to do.” A father of five, ranging in age from 10 months to 10 years old, he says he’s trying hard to be a good role model.

“I’m going to classes, studying Hawaiian mythology, history, language,” he says. “I want my kids to be raised more culturally aware. Lack of cultural respect is a big problem. We’re trying to get our identity back.”

Harp says he “felt happy” being on the undeveloped land above the Wailea golf course. “I felt good—better than sleeping or walking at the mall,” he says. “I want to bring my kids. I seen plants I never have seen before. The maiapilo, it has an unreal smell.”

Looking mauka with Maiapilo bush in foreground. Close up of Maiapilo flower. Photos: Rob Parsons |

|

|

At a Wailea 670 hearing a few weeks earlier, he said he just listened the first day, and was glad to have an extra day to listen and learn. Speaking at the next meeting, he told the council members he’s concerned about water and “sugar-coated” affordable housing and that he doesn’t want to see more building on these places. “Isn’t it worth fighting for?” he asked.

“Everything’s so Western now,” he says. “If you wanna go kanekapila (Hawaiian slang for backyard talk-story and playing music), you gotta go to Moloka’i. Everybody like make this their place. That’s why people stay snappin’. When I grew up, it was always about who could kick whose ass. Our success rate was low. You feel lost if you leave your homeland, but you feel displaced here, too.”

Harp grew up in a variety of places, often in government housing. But he says Wailuku is home. He says places he once enjoyed, like “Ponds” in Happy Valley, are now gone, due to the water diversion of ‘Iao Stream. Areas where they once gathered opihi andpipihi are also now gone. “I can't give that to my kids now,” he says.

“I’m proud to represent Hawai‘i,” he says. “I’m fortunate to own a business, and I’ve worked really hard to be a good artist. Hopefully we can be inspirational for more people. The key is to give more than you take. That’s real aloha.”

Samson’s father, Isaac Harp, is the current president of PASH. A former commercial fisherman and project director with KAHEA (The Hawaiian Environmental Alliance), he continues to advocate for protection for the Northwest Hawaiian Islands through the ‘Ilio‘ulaokalani Coalition.

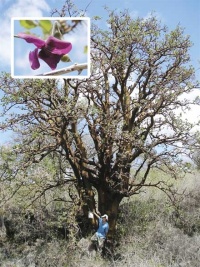

Grandfather Wiliwili tree. Inset: An Awikiwiki blossom. Photos: Dr. Lee Altenber |

|

|

Isaac Harp is “the hardest working, most self-educated guy I know,” Samson says. “He looks at the big picture, and fights for people he doesn’t even know. He’s like my hero.”

Samson’s cousin, Ilona Rahn, is the granddaughter of Charlie Keau. Born and raised Maui, she rattled off the names of a dozen towns she lived in while growing up all over the island.

At age 18, she moved to Moloka’i for two years. “That’s when I really got a feel for the islands,” she says. “They still fish, still hunt, still throw net. Nobody does that over here. When I moved back, I missed all that. And there are hardly any places left to do that here.”

She stopped by Samson’s tattoo shop the day after the first Wailea 670 hearing, and he urged her to come to the next meeting. “I just listened to the testimony,” she says. “But on break, I talked with a friend, then went back in and signed up to speak. I felt like we got one responsibility to this place because I’m Hawaiian. The land is part of us, and we need to save whatever we got left. Our land and the Hawaiian people is what makes this paradise.”

Rahn says her grandfather told her that all South Maui was once fishing villages, and asked her and her siblings to picture that in their minds. “So, walking around that day on the land was kind of trippy,” she says. “When I saw the mauka-makai trail, I was trying to envision what used to be there. I cannot imagine in 20 years from now how this place gonna be. I was thinking about moving away, but now I cannot. I know development gonna happen, but they gotta keep it to a minimum.

“If those wiliwili trees go, you’re not gonna get more, brah,” she continues. “We get strong ties to what’s around us—the ‘‘aina, the ocean, the sky. That’s what takes care of us.”

Like Samson, Ilona sports a large number of elaborate, Polynesian-style tattoos. She says she got a pu‘eo (owl) on her leg to remind her of when her grandfather took her to Keoneo‘io, and they would always see one flying there. The mo‘o (lizard) on her arm is her ‘aumakua (family protective deity).

The many tribal designs, she says, are “for certain times in my life. It reminds me of where I come from, and where my ancestors come from.”

Rahn told me how she saw Uncle Ed Lindsey and his wife Puanani at the Council meeting, and recalled dancing hula and paddling with their daughter while growing up. Lindsey later told her, “Girl it’s so good to see you guys come out here.”

“That felt good inside,” Rahn says. “We look up to them growing up, and now we standing next to them. That’s one privilege to me. I don’t see any good that can come from this [development]. Money is the root of all evil, right?

“It goes back to my grandfather,” she continues. “He fought to save Ma‘alaea, but they built it anyway. He was raised up in ‘Iao, but his ashes are spread in Nu‘u. They once had family land across from Big Beach, and he talked about preserving and stabilizing it. If I don’t do something now, then everything he did was for nothing.”

Chisa Dizon was born and raised on Kauai, and went to Waimea Elementary School and High School with several Ni‘ihau kids. “I learned the Hawaiian language, and picked up the Ni‘ihau dialect,” he says. “I learned to play the ukulele. I’m not Hawaiian, but I’ve grown up with it.”

At the Wailea 670 hearing, she told council members, “I’m a haole-pino,” with a haole mom and Filipino dad. But, she’s fourth generation living in Hawai‘i.

Dizon grew up with a subsistence culture of crabbing and fishing, and visited Ni‘ihau, where “they do fishing the old way.” The hike through Makena reminded her of Ni‘ihau, with the land dry and relatively barren.

Dizon has also studied Hawaiian plants and medicine. “The wiliwili trees looked like the last standing Hawaiian warriors out there, standing tall even in the harsh surroundings”, she says. She noted the wiliwili trees are very important in Hawaiian culture—both the wood, and the flowers, which can be used to brew a tea “stronger than kava.” Traditionally, the wood was used for fishing floats, to craft the ama (outrigger float) for canoes, and even to make surfboards. She says the maiapilo plant has leaves that can be uses like eucalyptus, as a remedy for sprains.

“Now the land up there is littered with golf balls and rubbish,” she says. “It should be protected. It’s all about aloha ‘aina, taking care of the land.”

Dizon said she heard about the Wailea 670 hearing “through the coconut wireless” and took a whole day off of work to attend and testify. She works as a radio station DJ and as a nail technician at a Kihei salon.

“I’m going to be doing a whole lot of networking,” she says. “We need to get people to educate themselves. I’m going to be rallying a lot of people. Mom always told me if I feel passionate about something, to speak up.”

This mauka-makai trail may once have connected Hawaiian fishing villages with upslope habitations. |

|

|

Recognizing the strong community sentiment running against the proposed project, three council members—Mike Victorino, Jo Anne Johnson and Michelle Anderson—cited a County Charter provision to ask for a meeting in the community plan area potentially affected by a proposed development. This is why the county will soon schedule an evening meeting on Wailea 670, to accommodate those unable to attend the daytime hearings in Wailuku. This will likely shift the momentum of the present discussions in the Council chambers.

Since the two hearings which allowed public testimony in late July, the Council Land Use Committee has met six more times, attempting to craft conditions of rezoning to make the Wailea 670/Honua‘ula proposal workable. Initially, Land Use Chair Mike Molina urged the committee members to hurry up, declaring, “It’s time to make a decision, one way or another.”

But South Maui district Council Member, Michelle Anderson, has strongly disagreed with that line. Instead, she’s methodically expressed inconsistencies and omissions in information provided to the committee. Anderson has called for the developer to build any “affordable housing” mandated by the Council within the project area and not—as developer Charlie Jencks has proposed—in a North Kihei light industrial site “by the Pi‘ilani Highway, and with no amenities, such as parks.”

Anderson has promised to help craft a number of strong conditions, insisted on a review of groundwater studies and for ocean water quality monitoring and has proposed that the county set aside all 110 acres of an a‘a lava flow supporting a remnant dryland forest habitat as a botanical and cultural preserve.

Dr. Lee Altenberg’s botanical study of the Wailea 670 area lists 20 species of Hawaiian plants present on the rocky area at the Southern end of the land. Among those species, awikiwiki and a variety of nehe are among the rarest, though neither has been listed on the federal list of endangered plants. Still, the Hawaiian dryland forest is listed as one of the top 10 most endangered ecosystems in the U.S., since only five percent of its former range throughout the islands remains today.

Pressed by testifiers and council members to preserve more than a tiny portion of this habitat, Jencks described the area as “not a contiguous area, but fragmented.” He said the topography is “more severe” and thus better for golf.

But Anderson, looking at her copy of the project map, disagreed. “It’s single-family and multi-family, and the wastewater treatment facility taking up 90 percent of the area, so what you just said is not even true,” she said during the hearing. “The Forestry & Wildlife survey is outdated and wholly inadequate. It’s a crucial and vital ecosystem.”

Council Chair Riki Hokama became particularly incensed over discussion of a private golf course as an exclusive perk to homeowners. “Who are we building for?” he demanded. “I’m tired of restrictions for our people of where they can’t go.”

Now it appears the Land Use Committee will be heading back to the drawing board, to accept more public testimony at the evening meetings in Kihei and again when the matter returns to the County Council itself for deliberation.

When that happens, our decision makers will surely hear from a number of passionate born and raised local residents, called to action to protect what remains of their ancestral culture. “Whatever we have left is not too much, and they like take that away, too,” says Ilona Rahn. “It’s gonna change everything what Hawai‘i is and stands for.”